I've been investing a lot of time and energy over the past couple of years learning how to create things - drawings, animations, music, 3D models, video games, the works - and the ultimate goal of all this is to get a story published in some form. But there's one very key thing preventing me from fitting all these pieces together: I am terrible at coming up with stories.

Don't get me wrong, I can write - I can describe characters and places with flowery language, I can come up with jokes and everything - but I have no idea how to string all these characters, places and jokes together into one coherent narrative with a beginning, middle and end. If you gave me a pre-established story or plot outline and asked me to sprinkle it with dialogue or worldbuilding or gags, I could probably do so, but if you asked me to come up with a whole story from nothing, I'd be lost.

So I've looked high and low across the Internet to find some guides on how to structure a story. Here's some of the stuff I've learned from various sources. I'm mainly focusing here on how stories are structured from beginning to end - there's a lot of other things I could mention about character and worldbuilding, but I don't want to make this blog post too big.

Before I start, just bear in mind that none of what I'm saying here is gospel. There is no objectively "right" way to tell a story other than the way you think is best. In fact, a lot of what follows might come across as self-contradictory. If you look up writing advice online, you'll get a lot of different perspectives from a lot of different storytellers, and what works for one story vision might not work for another. So don't just take everything at face value - pick the stuff that you think works best for you or the story you're trying to tell. Or better yet, see if you can do the opposite of what you're being told, or take it in a new and unique direction.

Three-Act Structure

Fiction seems to like the number 3. I don't know why, but 3 is the number that always seems to crop up. Maybe it's because it's the lowest number you need to both establish a pattern and then break it. Recurring jokes, for example, usually only repeat three times: the first time to introduce the joke, the second time to surprise you by its return, and the third time always has some kind of twist on it to keep it fresh. Any more than that and it's probably not going to be as funny; it's like the comedy equivalent of diminishing returns.

Most stories seem to be separated into three parts, too - a beginning, a middle and an end. At the beginning, we set up the characters and the big problem they're facing. In the middle, the characters try to address the big problem, but they keep messing it up - or they have to solve a bunch of smaller problems before they can tackle the big one. At the end, the characters finally solve the big problem, usually learning some kind of lesson on the way.

Act One: Setup

This is about the first quarter of the story or first twenty minutes of the film. First things first, we answer the questions of who, what, when, where and why:

- Who are our main characters?

- What's the story going to be about (what's the big thing they're trying to do for this story)?

- When does this story take place (does it take place in a different time, or is there some kind of time limit to the quest)?

- Where does this story take place (what's the setting like, and where will it go from here)?

- Why does this story take place (what causes the central conflict, and why can't the protagonist just ignore it)?

The first part of a story - the run-down of what our protagonists and their world are like - usually answers the who, when and where. About halfway through the first act, the "inciting incident" occurs that gets the characters on-track to carry out the main story mission, so it's here we'll get the what and the why. The rest of act one is usually dedicated to giving the protagonist all the equipment and training they'll need to start the journey proper, so we can go straight into act two and right into the meat of the story.

A general rule of thumb is that by the end of the first ten minutes of the film (or fifty pages of the book), the audience should have a pretty good idea of what the story's going to be about - any longer than that and they might get bored of waiting.

Act Two: Confrontation

This is the middle part of the story, where the protagonist starts making a direct attempt at solving the story's main problem. Obviously they won't solve it right away - maybe it's something that takes a long time to do, or they bungle the first few attempts which causes things to get more complicated. In the meantime, they'll start building their relationships with their co-stars as they navigate the obstacles and incidents that start cropping up. If there's a villain, this is usually the part where they start messing with the hero.

What you usually find is, right at the midpoint of the story, the character begins to hit a stride and feel like they're getting somewhere. They might find themselves on the cusp of achieving their ultimate goal, or at least feel like they can manage it even if it's still a long way off. Then it all goes wrong - the protagonist makes a really stupid mistake, or the bad guys decide to roll up their sleeves and stop holding back. At this stage you might find a sort-of pre-climax climax - a big, exciting sequence in the middle, like a round-one fight between the good guys and the bad guys. In this event, what usually happens is the good guys lose, and everything the hero was working towards is suddenly ripped away, leaving them on the verge of completely giving up by the end of act two.

Act Three: Resolution

Act three usually begins with our protagonist down in the dumps, still reeling from their lowest point. But they can't just give up completely (for any longer than five minutes) or we won't have any more story. Something has to pull them out of their rut - maybe they remember an important clue they've overlooked so far, or one of their friends encourages them to get back in the fight. If the character has any flaws, this is usually the part where they figure out precisely what they have to do to overcome them.

Then comes the climax. This is described as the most exciting part of the story, but it'd probably be more accurate to say it's the part with the highest stakes. This is usually the protagonist's very last chance to get what they want - if they slip up now, they're not bouncing back from it like last time.

Whether they succeed or fail, the final part of the story is usually the aftermath. This shows a little of how the character and the world have changed since the climax and adventure. Usually the protagonist goes on to apply in their personal life a valuable lesson they've learned while on the journey.

(By the way, every so often I'll talk about the character learning a "lesson" or a moral. I don't necessarily mean an educational one, or a message you want to impart to the audience - I just mean one that the character needs to learn in order to develop. If the character didn't have anything to learn or any flaw to overcome, they'd have their ultimate goal right from the beginning. The very fact that they have to even take part in the narrative suggests that there's something they need to understand before they can have what they want).

Booker's Seven Basic Plots

Christopher Booker in his 2004 book The Seven Basic Plots: Why We Tell Stories proposes the existence of seven basic story plots that show up in most fiction. Each of these plots could be said to have the same overall meta-plot:

- Anticipation: the hero is first called upon to undertake the adventure

- Dream: the adventure begins, and the hero actually does pretty well at first

- Frustration: the hero has an encounter with the main villain and suddenly stops doing so well

- Nightmare: everything starts going wrong and it doesn't look like the hero will win out

- Resolution: the hero somehow overcomes these problems and completes the adventure

The seven plots themselves are as follows:

- Overcoming the Monster: there’s an unlikeable entity or force running around and someone has to deal with it.

- It begins with an evil of some sort posing a threat. It’ll either be a predator (who just aggresses people out of nowhere), a holdfast (who’s doing this to protect something) or an avenger (who’s bitter about the fact that someone took the thing they were protecting).

- The hero begins to train up and make preparations while they approach the threat or the threat approaches them.

- When the danger does show up, no matter how much the hero’s trained, it’ll wipe the floor with them.

- The hero finds the source of the monster’s power and makes a desperate play to overcome it in the face of the odds.

- It somehow works, and whatever power the monster had over the setting and its characters is broken.

- Rags to Riches: life is tough, but a hero who sticks at it ends up making things better.

- The hero starts off unhappy or dissatisfied, and the antagonists are usually the forces keeping them in that position.

- Somehow, they are upheaved from that position and enjoy a quick initial success, encouraging them to hold out for more.

- Before long the protagonist might be on a roll, but eventually something will go wrong. Maybe it’s a stupid mistake, maybe they got complacent or carried away, maybe the antagonistic forces from earlier are reasserting themselves – but they’ve suddenly lost everything they were working towards.

- If they’re going to bounce back, the hero needs to rely on their own natural skills and the lessons they’ve learned – they can’t just coast on the wealth, genies or other freebies they got earlier, otherwise the whole thing will just repeat itself. By recognizing the importance of their own behaviour in the equation, the hero develops a sense of independence.

- Having proved they’re willing to put in the work where it counts, the protagonist gets the better life they were looking for.

- The Quest: you and your buddies are going to have to go through more than you bargained for to acquire this thing you want or need.

- There’s something that the hero needs – or really wants – and the only way to get it is to leave their familiar space. Usually they have some allies to bring along and a starting clue to set them off in the right general direction.

- The Quest story is usually episodic in nature, and made up of various anecdotes concerning the obstacles the heroes face as they search for what they’re searching for. These often include:

- Random encounters with enemies, disasters and other hang-ups.

- Temptations or illusions that’ll lead them down the wrong trail unless resisted.

- A dead-end point where the only way ahead is to navigate a really difficult path between two dangers you can’t ignore.

- Any of the above can yield further clues about the treasure’s location, but the most vital clues are usually hidden right in the midst of some very dangerous and forbidden territory (for example, the underworld, where only the ghosts have the knowledge you need to find the treasure).

- Once the heroes are on the home stretch and the goal is in sight, the obstacles they face begin to escalate – some might even come out of left field, like an antagonist suddenly influencing the journey, or something else they couldn’t have prepared for.

- The final obstacles between the heroes and their prize tend to be threefold: the first is one that tests everybody’s skills, the second whittles it down to the most-developed members of the team that need to learn the most pressing lessons, and the finale is usually reserved for the main character on their very own.

- Following a narrow escape, the heroes finally have the thing they were looking for, which the epilogue promises will renew their lives in some way from here on out.

- Voyage and Return: maybe a couple of half-hours in a far-off land with different rules will change your perspective of things back at home.

- The hero usually starts off with some kind of flaw or restriction that keeps them from developing in their usual environment – until something sudden and unexpected uproots them to a different environment entirely.

- After an awkward period of adjusting to this puzzling and unfamiliar world, the hero will eventually acclimate to their new environment, and even come to enjoy the new digs. But no matter how much they hit their stride here, it will never feel truly like “home”.

- Something begins to go wrong. A darker side to this new world starts to manifest itself. Maybe an evil force is threatening it – or maybe the world itself was never nearly as friendly as it presented itself to be.

- The hero’s character flaw may have become far too indulged by the time the threat is impossible to ignore, and will hamper their ability to address the threat.

- Only by getting over their flaw will the character be able to push back the danger threatening the land – or if the land itself is the danger, make their swift escape back to their home world. Either way they return to “normal” life changed by their experience in some way.

- Comedy: a lot of comedy is built upon miscommunication – a misunderstanding that begets hijinks and other misunderstandings. Eventually the confusion grows untenable and has to be set straight.

- The setting is usually rife with confusion, or is about to become rife with confusion. People get into various escapades as they try and navigate these grey areas, as well as each other. The goofiness belies the fact that they can’t reach out or get through to each other.

- Murphy’s law begins to take root as the screw-ups become more dramatic. Flashes of better judgement are usually ignored – often by the main protagonist themselves – until the setting reaches an unsustainable rock-bottom of absurdity.

- Eventually, something makes the characters begin to think about things differently to how they did before. Suddenly they can look at things more rationally and clear through some of the misapprehensions, helping people wise up and finally ease their stresses.

- Tragedy: stories where we follow the villain, exploring their origin and how it is they’re ultimately toppled, usually by getting the better of themselves.

- Like in the Rags to Riches storyline, the main character wants or needs something they’re not getting. Where they differ is while the heroes hold out for hope, these antiheroes tend to focus more on feelings of resentment.

- Eventually, the protagonist does something bad – that ends up getting them closer to what it is they want. Seeing the correlation, they end up committing themselves to the ill-advised course of action. At first, things go well for them – they get away with all the stuff they do and no one seems any the wiser.

- Then, cracks start to show: maybe they got careless, maybe somebody’s onto them, maybe something changes they didn’t account for. In any case, these new difficulties have them in a bind, and the only way to keep living the high life is to perform progressively worse and more desperate actions.

- Of course, covering up crimes with even worse crimes isn’t a sustainable plan of action, and soon everyone’s cottoned on to what our antihero’s been up to. At the end of their tether, the protagonist knows they’re about to get their just desserts – but they’re hardly thinking straight, and this is the point they’ll usually commit their most destructive acts (both to others and to themselves).

- Eventually the protagonist is caught and sent down, often because of a glaring oversight their more innocent self would’ve considered. We might feel bad about the circumstances that first led them to these choices, but we know they picked the wrong ones every time.

- Rebirth: kind of the opposite of the Tragedy – instead of a hero devolving into a villain, these stories deal with unpleasant people who learn to be a bit nicer.

- Starting off, the hero either forms a bad habit, or has a bad habit to begin with.

- This bad habit might work out well for them at first; but in time, it begins to have adverse effects on their own wellbeing and that of others – though the protagonist may not know or care.

- Eventually, they become addicted to their bad habit, even when it stops paying dividends – their lifestyle becomes unsustainable and everyone around them starts cutting ties.

- At this point it falls to a certain someone (often with extraordinary insight) to pull our protagonist out of the rut they’re in. This figure helps the protagonist reflect on their behaviour and find a better way of doing things.

- Reminded of what’s important, the main character frees themselves of their bad habit, and end up making others and themselves a lot happier for it.

The Hero's Journey

Have you ever wondered why every animated film seems to have the same plot structure as the first SpongeBob movie? You know, the heroes have to leave their familiar environment and go on a journey to lands beyond in search of some kind of treasure that will hopefully fix a problem back at home? Philosopher Joseph Campbell proposed in his 1949 book The Hero with a Thousand Faces that the most common stories told across cultures are about an ordinary person leaving their ordinary world to have an adventure in some kind of unfamiliar world. Feature-length adaptations of TV properties tend to go down this route because we’ve seen enough of their “ordinary” life in the show – you’re going to have to provide something different if you want to justify getting people to sit in a packed theatre for an hour and a half.

I often call these stories "otherworld" stories, because they involve characters going to what to them might as well be another world. This "otherworld" doesn't necessarily have to be an alternate dimension or something - it could be a wondrous fantasy world full of magic and mystery, or it could be no more mysterious than a new job the protagonist has signed up for. The key ingredient is that the main character is unfamiliar with this new environment, and thus has no control over it.

The adventure is usually split into three segments (three acts, if you will):

- Departure (leaving the mundane world behind and crossing over into the unknown)

- Initiation (learning to navigate this strange new world)

- Return (going back home, usually bringing with you some sort of keepsake)

Departure

Unusual Birth Circumstances

The story might start by delineating some unusual circumstance about the hero’s birth, upbringing or nature. Maybe they figure into some kind of prophecy, maybe their family line comes from the other world. In any case, our hero in the ordinary world may turn out to be not 100% ordinary themselves.

Ordinary Life

The story usually begins with a quick run-down of the hero’s ordinary life in their ordinary world. Maybe it’s a pleasant world, and the conflict comes from their way of life being threatened. Maybe it’s not-so-pleasant, and the hero is looking for a chance to improve it. It can be a bit of both – what you often find is that the hero is below-average in some respect and doesn’t quite “fit in” to their home world (which goes back to them possibly not being entirely native to it to begin with).

Call to Adventure

Then comes The Call. Something about the hero’s ordinary life changes, if only by a little, that opens up a course of action that, if followed, will put them on a collision course with otherworldly adventure. Maybe they’re called to step up to the plate. Maybe they just blunder into something by complete accident. Maybe they’re just going about their ordinary life when suddenly something weird catches their eye – a meteor falling overhead, or a cartoon white rabbit scampering by.

Refusal of the Call

Sometimes the hero will jump at the chance to do something different, but what you often find is they’ll dig in their feet and keep focusing on their normal life. This showcases the negative aspect of the normal world – when they’re finally given the chance to do something great, the normal world becomes a millstone keeping them from exploring their full potential. The story must disabuse them of this by making their ordinary life unsustainable - something that makes it clear whatever’s going on is their problem now. Even if they do jump at (or glibly resign themselves to) the Call, they’ll struggle at first because they’ll still be trying to apply normal-world ideas to an abnormal situation – remember, the call they’re refusing isn’t necessarily the call to go to the otherworld, it’s the call to change.

Supernatural Aid

Once the hero’s committed to the otherworld (consciously or unconsciously), they’ll find they can’t just run into the unknown unprepared. They’re going to need that initial leg-up, and this is where Supernatural Aid comes in. A mentor figure, usually some kind of Weirdy McBeardy wise old owl type (definitely reverential, often supernatural), imparts some advice on how to get to and around the magical fantasy world the hero’s headed to, and often hands them some kind of mystical trinket that might not seem all that relevant but may come in handy later.

Crossing the First Threshold

The First Threshold is crossed when the hero makes their first conscious, willing decision to separate themselves from the normal world and enter into the fantasy world. They may already run into their first obstacle in the form of Threshold Guardians: forces or things that call into question whether the hero is actually committed to the journey. In meeting the guardian’s challenge, the protagonist wilfully commits themselves to the road they’re on, or makes a decision that reflects that commitment.

Belly of the Whale

The problem is, fantasyland will kick your ass. The hero isn’t likely going to win their first few fights, and whatever new allies they make are going to seem so much better at this than they are. Rather than triumphantly carve their way through the otherworld, they’re going to be completely overwhelmed by it at first. At this point the hero must realize if they want to make it here, they’re going to have to change something about themselves. This sets them on the path to becoming a different person than when they came in. If they’ve been considering turning around and going back home, this is the point where they commit themselves to make the change – it’s death or glory by this point.

Initiation

The Road of Trials

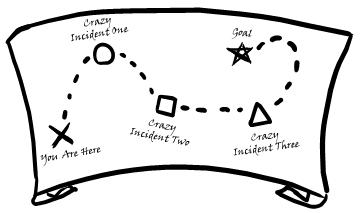

Now it’s time for the meat of the story – the shenanigans the characters get into on their way to the ultimate goal. Here’s where they make new friends, meet new enemies and have encounters that test how much they’re growing into the person they’re trying to become. For some reason, there’s usually at most three major incidents that take place before the story reaches its third act.

Meeting with the Goddess

But perhaps the biggest test the hero faces is whether or not they can hit it off with their love interest. Throughout the trails they face, the two grow closer to each other. The idea is that a romantic interest leads the hero to amor fati: the love of fate; to embrace all aspects of life, including suffering, as valid and necessary. If the hero lacks a romantic interest, this role may be fulfilled by a close friend or some other character they seek the approval of – someone who gives them a reason to keep going.

The Temptress

This might be the reason why seductive temptresses make for great villains, since they give the hero a compelling reason not to keep going. For some reason this is the one trap heroes usually seem to fall for, leading them to alienate their love interest or muse. We can’t judge the femme fatale too harshly, though: women are thought in the old myths to represent life itself, which includes those perfectly natural carnal urges that we like to ignore or reinterpret. The attractive bad girl forces puritan heroes to confront the fact that these feelings are an important part of who we are, and until they come to terms with it, life and the acts of life the villainess represents will feel intolerable to the hero.

Atonement with the Father

At some stage late into the story, the hero is going to have to reflect on whatever holds the most power over their life. This may involve atonement – the correction of wrongdoing. This is also probably the biggest paradigm shift the character will have in the story: all the decisions they make after this will be based on this revelation. If there are any mysteries pertaining to their life, this is where the protagonist will get all the answers and decide what to do with them.

Apotheosis

If this reconciliation goes well, the protagonist reaches Apotheosis: this is the point where they embrace their new understanding of themselves and the world. This is the shift in personality all the trials so far have been working towards.

The Ultimate Boon

With this newfound power and insight, the hero finally snags the thing they were looking for all this time. The value of the Ultimate Boon doesn’t lie in what it is, but what the protagonist is able to do with it post-apotheosis. If they consider swiping it for themselves or using it self-servingly, it might serve as one final temptation.

Return

Refusal of the Return

When it’s time to come back home, the protagonist might not be sure if they even want to leave. They’ve grown accustomed to the new world they’re in, and they need to be reminded that there’s people back at home that could benefit from using what the protagonist has found (internally or externally).

Magic Flight

With the boon in hand, the hero must finally make their way back to the ordinary world in what is known as the Magic Flight (and it has to be magic because the return journey is never as interesting as the adventure itself). If there’s a main villain that hasn’t been beaten already, this is the part where the final fight takes place.

Rescue from Without

On occasion, the hero can’t fully return to the ordinary world without someone bridging the gap. Maybe a powerful individual has to wake them up from their dream – perhaps someone they’ve met in the otherworld who owes them a solid, or someone from the real world reaching out to them.

Crossing the Return Threshold

It’s always a weird experience coming back over the Return Threshold. First of all the hero has to judge whether the crazy adventure they just went on was real. Then they have to re-acclimate to boring normal life – it’s hard going back to being Joe Schmoe in one world when you were cock of the walk in another, and this is especially true if the protagonist was never the most popular or successful guy around to begin with.

Master of Two Worlds

Then it comes to the point where the protagonist remembers it’s not about fitting in – it’s about sharing what they’ve learned and picked up from the otherworld. They become a pioneer in their own world for new and exciting prospects, having attained mastery of both worlds.

Freedom to Live

The ultimate reward of the quest – for both the protagonist and everyone else in the ordinary and magical worlds – is the Freedom to Live. This roughly means the characters have learned to live in the moment and appreciate life as it comes, neither fretting about the past nor worrying about the future. Happily ever after isn’t just enchanted palaces and fancy ballgowns: it’s knowing that whatever the future holds, you’ll be there to face it.

Save the Cat

In his 2005 book

Save the Cat, Blake Snyder provides a general structure for stories very similar to the Hero's Journey. He proposes fifteen "story beats" that make up your average 110-page screenplay - that means if you go by the general idea that one page of screenplay equals one minute of movie time, you'll have a movie that's about two hours long by the end of it. This can, of course, be adapted to other types of media with longer or shorter runtimes.

- Opening Image: your first line, what the story opens up on. It’s something that grabs the audience’s attention – you rarely just start with the protagonist just doing their morning routine (there’s usually some kind of vignette that precedes it).

- Theme Stated: in the protagonist's ordinary life we can usually see subtle hints at what about them needs to change, or there’s some kind of gesture towards the overall theme of the work (the “theme” is the moral, basically – if politics is the topic, then the “theme” is what your own particular political view is).

- Set Up: the first ten pages of your script; both the run-down of the protagonist’s ordinary life and an introduction to the characters and forces that will come to influence it – if they’re from the otherworld, they may only be hinted at.

- Catalyst: the Call to Adventure. Something in the protagonist’s ordinary life changes that allows the otherworldly forces to meet with them.

- Debate: the Refusal of the Call. The protagonist will likely be unsure of exploring this changed “something” in their status quo – or if they do jump at the chance for a new adventure, they’ll find they’re not very good at it.

- Break into Two: The First Threshold. The protagonist makes a decision that properly commits them to the otherworld. From this point onward, they’re officially “on the quest”.

- B Story: at around page 30 of the script, the main subplot is kicked off. While the A story is about the protagonist and their journey, the B story tends to be about the supporting characters and their relationship with the protagonist, often with parallel themes to the main quest. What you often find is the B plot is a more grounded, realistic look at the work’s overall message, while the A plot is more of an action-packed fantastical metaphor.

- Fun and Games: the jokes, the bits, the spectacles. The first half of the second act can usually be boiled down to “yadda yadda yadda”. These are the shenanigans the protagonists partake in on their way to the home stretch. They don’t necessarily have to be jokes, it can just be the protagonists doing cool things in cool places with cool people. A lot of writers start off with ideas for unrelated anecdotes and struggle to try and fit the story around it (and by "a lot" I mean me).

- Midpoint: the middle part of the story, at about page 55 of your script. Beyond this point, you’ve got forty-five minutes of runtime left, so everything new you introduce here better be plot-important.

- Bad Guys Close In: the second half of the second act is where things start to really go wrong. The forces arrayed against the protagonists become directly involved, throwing them off-balance as fatal mistakes are made.

- All is Lost: at about page 75, the protagonist experiences some kind of loss owing to the previous events. They might lose a friend, an item, an ability, or their own self-respect if they feel they’ve gone against their own morals. Whatever they’ve lost, it was something that galvanised them throughout their quest – without it, their confidence in being able to carry out the mission is sorely shaken.

- Dark Night of the Soul: here is the Atonement with the Father, where the protagonist has to reflect on what precisely their problem is.

- Break into Three: after enough soul-searching, the protagonist will remember a useful piece of information – something that rallies them and restores their confidence, so the quest no longer seems impossible.

- Finale: the last 20% of your story (from about page 85 to 110 in your script) is usually dedicated to the final boss. For characters, the third act is usually a thematic synthesis between what they already know (from act one) and what they’ve learned over their journey (from act two). This stage can be further broken up into five segments:

- Gathering the Team: first things first, the hero will gather up all the things they need to tackle the final challenge. Surviving allies will likely be called upon, and if there’s any turbulence between them owing to earlier events in the story, now’s the time to make up for it and bury the hatchet. This is also where a plan of attack is formulated.

- Executing the Plan: the fight begins proper, as the protagonist with all their tools and allies rushes in to address the problem head-on. And at first, it usually goes great: the bad guy’s caught by surprise, the hero is using their innate and learned skills to the fullest extent and is coasting off the high from their resurgence at the end of act two.

- High Tower Surprise: at some point, the bad guys will get the upper hand. Maybe the protagonist is lured into a trap, or maybe they make a glaring mistake, or the villain hulks up with some unforeseen superpower, or something else unforeseen prevents the hero from carrying out their initial plan of action.

- Dig Deep Down: the protagonist has to do some last-minute soul-searching and figure out a new plan – usually a hastily-improvised one based on addressing their own central flaw. This is where they have their big lightbulb moment, or play their emergency ace-in-the-hole.

- Execution of the New Plan: in carrying out this new, perhaps impulsive plan, the protagonist has demonstrated they’ve finally gotten over their biggest flaw. Now they’re their best self, their thinking-on-the-fly usually ends up successful, achieving their ultimate goal. If it doesn’t, or it’s a Pyrrhic victory, then it suggests something allegorical about the story or theme.

- Final Image: the last image of the film, or last paragraph of the story, usually reflects the overarching theme and puts a little bow on the overall message. Some final images counter-pose the opening image to reflect the change that has taken place.

Fun with Fun and Games

As I said, the part of this model I probably struggle with the most is the "fun and games" part - or the "Road of Trials" in the Hero's Journey model. I can come up with wacky antics, but actually putting them in the story is another matter.

But a good place to start is by asking "what's your story about?" The basic "logline" of a story (summing it up in one or two sentences) can be viewed as a quick run-down of the story’s core axioms:

- Hero: somebody that the story follows

- Goal: what the hero’s trying to do, what ultimate wish motivates their decision-making

- Obstacles: what’s preventing the hero from achieving their goal

- Stakes: a reason why the hero can’t just give up in the face of these obstacles

The Fun and Games segments – the first 25 minutes of act two in a movie – fulfil on the “promise of the premise”. They’re usually the main selling point of the movie, and provide the audience with the spectacle they came here for. If your movie’s about superheroes punching each other, here’s where most of that punching takes place. If your movie’s about a particular high concept, here’s where you explore the furthest limits of that concept.

The Fun and Games segment is basically the platform for the bulk of the jokes (or if not jokes, then the other cool stuff you wanted to make the movie for – whatever the equivalent of “antics” is in other genres) and is relatively light on plot advancement. But that doesn’t mean the plot just stops – they’re still going for a goal and facing down obstacles. One could use a similar structure to the five-point Finale in planning your shenanigans phase:

- The protagonist will plan out how they’re going to tackle the challenge ahead. Having yet to get over their central flaw, they’re probably going to make the wrong decisions.

- The protagonist then faces down their first obstacle and tries to carry out their plan of response.

- It doesn’t work. Or it does, but then something unexpected stops it in its tracks.

- The protagonist has to think on their feet and come up with a new plan. This plan will still be filtered through the character’s flaw, focusing on what they want rather than what they need.

- The protagonist will somehow muddle through, overcoming the obstacle more in spite of their planning than because of it. Or it might go well owing to a flash of character development, but the significance of this paradigm shift will likely be ignored until act three.

These five points can be applied on an individual basis to each obstacle, or they can be taken for the whole Fun and Games segment (the hero may overcome their first obstacle with aplomb, but then something out of nowhere forces them to recalibrate their whole strategy going forward).

In road movies, what you often find is that there’s three major incidents or set pieces that take place between the start of act two and the Atonement with the Father that kicks off act three. What you also tend to find is that while the first two “levels” (to use video game parlance) are for the most part squarely Fun and Games, the third “level” often includes elements of the Bad Guys Closing In, as external threats to the characters begin to catch up.

The midpoint that comes at the centre of the story (in this case after the second level and before the third) often manifests itself as either a false victory or a false defeat: either the hero thinks they’ve got it in the bag and are about to walk into a rude awakening, or the hero already feels like giving up and the Bad Guys Closing In puts the screws on them and encourages them to shape up.

Dénouement

Another thing I struggle with is how exactly to "end" the story. I don't mean how the villain is defeated or how the main mission is achieved, I mean what I'm going to fill the last scene with. Usually in stories there's at least one scene after the climax that winds down the action and finishes off the story. This is often called the dénouement ("day-new-mon") from the French for "unknotting", because this is where you pick apart all the story's plot threads and loose ends, then tie them up in a bow.

This usually means any conflicts that haven't been resolved yet are finally dealt with. If anyone's been lying throughout the story, this is where they're found out, and if anybody's keeping secrets, now's the last opportunity they'll get to share them. Any big questions or mysteries the story poses need to be answered by at least this point if they're going to be answered at all.

Another thing dénouements do is showcase the change that has taken place over the story, and give us a look at the consequences of that change. We might see a character get to practically apply the lessons they've learned from the story into their everyday life. We might see the love interests get married, or just enjoying each other's company. If the setting became damaged in the story, we can see it start to heal. If someone died, we might see their funeral. If it's a horror story, you might even add a grisly twist ending, especially if the main character didn't really overcome all their flaws: if your story's about vampires, it could end with the surviving main character gratefully going back to their ordinary life, only to look in the mirror one night and find their reflection has disappeared.

The Save the Cat method ends on a "Final Image" that often ties in with the theme of the film. This can be one last shot or one last scene that shows how the characters and their world have changed. It's often a mirror of whatever the opening scene was - so they both serve as a "before" and "after" snapshot for the setting. This can be metaphorical - maybe if your opening shot is an image of the night sky, your closing image might be that of the Sun coming up. The final image might actually be the same image that you started with, just given a new meaning.

Here's some common ending images - also known as

hat-and-coat shots (because it's time the audience grabbed theirs and left) - if you're struggling:

- Characters walk/ride off into the distance, off-screen or otherwise away from the camera, signifying them leaving the audience behind

- Zoom or move the camera away from the characters, so it looks up into the sky or out onto a vista, showing that we're no longer focusing on the characters and are now focusing back on the world (as in, the real world - the one the audience really should be getting back to right now)

- The style of sky you're panning up to can suggest something about the mood; so a clear blue sky suggests freedom, a cloudy sky suggests uncertainty, while a starry night sky suggests tranquillity

- Freeze-frame or cut out the camera just when something significant, disastrous and/or funny is about to happen

- Freeze or zoom in on a significant object, like for instance a photograph

If your story is a comedy, you might end on a joke. Sometimes the last punchline is followed by all the characters laughing, even though the chances are it's probably the weakest joke in the whole thing.

Slice of Life

So far, we've been focusing on big adventure stories with big fights between good and evil... but what if your story isn't like that? Maybe your story is a bit more down-to-earth. A "slice of life" story (at least as I understand it) is one that depicts mundane, everyday experiences, and is usually about the daily life of the main characters. You know, something like The Simpsons - there's no big adventurous concept there, it's just the day-to-day exploits of a quirky family living in a quirky town. Unlike the Hero's Journey, which uproots characters from their normal life, slice of life stories are about what they consider their normal life - even if it doesn't seem that normal to us.

What you often find is that the story beats in a slice-of-life story might actually be quite similar to the Hero's Journey/Save the Cat story beats, just with lower stakes. The "villain" of a slice-of-life story might just be an obnoxious co-worker who keeps parking their car in the main character's space. The stakes aren't world-ending, they're not going to avert a major crisis by getting this guy to park somewhere else, it's just something that will continue to be annoying until it's dealt with.

The "Call to Adventure" might be a call to something mundane, like a talent show or a new job opportunity. If the protagonist "refuses" this call, they're not likely to have their house burnt down - maybe someone they really don't like is entering the talent competition, or their microwave gets busted and they could use the extra money. Getting into conflict in a slice-of-life story is often more a matter of "want" than a matter of "need".

The "All Is Lost" moment doesn't have to be life-ruining - just a complication that upturns the characters' plans. Maybe it turns out someone else at the talent show happens to be doing the same act the protagonist is trying to do, but much better than they ever could. Maybe their new job is great at first, but then they get saddled with a massive responsibility that they just can't cope with.

By the end of the story, what you often find is that everything "goes back to normal", and the protagonist goes back to their normal everyday routine, ready to have something else stupid happen to them next episode. That's not to say they don't achieve their goal - it's a goal that will make them feel good, but won't change their lives too drastically (a nice trophy to keep, or just the satisfaction of being back to the job you're good at). However, if they don't achieve their goal, it's no big deal - they're not dead by the end of it - and if the problems of the episode were caused by their own stupidity, then the protagonist has something to learn from. Slice-of-life stories often end with the protagonist a little wiser about a subject than they were starting out... at least until the next episode.

In an episodic series without any underlying story arc, you're not under any obligation to have any of these lessons or character development stick... but viewers will be impressed if you do. Even in a series with no continuity, if the same exact character keeps getting in the same exact situations for the same exact reason, your audience might start to tire of it.

Scenes

It's all well and good knowing the general idea of how the story turns out, but how do we translate that into individual scenes? It's a huge problem that I have - I know what I want my characters to do, I even know what jokes I want to put in... but I don't know how to take all that and stick it into a coherent scene. I don't know actually what to write. If I know some characters are going to get into a fight, well, how do they start the fight, and how does the character I want to win actually win?

Well, a few sources I've seen split scenes into two types - the "action" and "reaction" scene. The difference between them is simple: in the action scene, characters are doing something, while in the reaction scene, characters are reacting to something that's already been done. These scenes tend to alternate between each other - so you have an action scene where the characters do something, a reaction scene where the characters react to what just happened, then another action scene where they do something else.

The action scene can be separated into three pieces:

- Goal - what's the character's goal here? What are they trying to do in this scene?

- Conflict - what's standing in the way of the character achieving their goal? How does the character try and navigate this obstacle?

- Disaster - what's the outcome of the scene? Does the character get their goal? If not, what do they get instead? A clue for how to get the goal next time? A thorough pummelling? Can they try that same goal again next scene or are they just going to have to move on?

Meanwhile, the reaction scene can be split into three as well:

- Reaction - how does your character think the last scene went? Are they doing anything while they're reacting?

- Dilemma - what's the next move your character is considering? Are they trying to think of a new way of dealing with the obstacle? Are they worrying about the next one? How far are they from a complete breakdown?

- Decision - what does the character decide they're going to do next? Whatever they decide will give them a new goal with which to approach the next action scene.

In shorter-form rapid-fire fiction, like an eleven-minute cartoon, you can combine the two scenes together. A scene can kind of ping-pong between action and reaction: at the start of the scene, the character tries to do this, which causes this to happen, which makes the character react like this, which makes this happen, and so on and so forth until the character either gets their scene goal or is blocked out from getting it entirely.

Scenes like this can also follow the rising-falling action pattern of the whole story. What you often find is that the longer the scene goes on, the harder it becomes for the character to achieve their scene goal. The "climax" of the scene is that clinching decision the character makes that either gets them their goal or renders it impossible to achieve.

That's about all I can think of for story and scene structure for now. Remember, none of the above are hard-and-fast rules, they're just suggestions based upon stuff that you often see in fiction. Let me know if you have any other ideas on how to decide the content of a plot or scene.

Comments

Post a Comment